Bullish on Art

Good-bye Paris salon—hello Wall Street hedge fund

BY JOSEPH HART

VAN GOGH: $12 million. Rembrandt: $13 million. Vermeer:$30 million. Gauguin: $39 million. You wouldn’t guess it from these rock-star price tags, but all these artists died in poverty. And for every Gauguin that now sells for a mint, there are thousands of Robert Bevans. The obscurity of Gauguin’s friend and contemporary matches his postmortem earning power. Bevan is known chiefly for his renderings of horses, which still sell for just a few thousand dollars apiece.

Concerned that most artists still starve, even when their paintings eventually fetch millions, a few financial wizards have hatched a plan to erase the words died in poverty from the artistic vernacular. They’ve created an artist pension trust, a kind of 40 1(k) that asks participants to contribute not their earnings, but their art. According to Wired (April 2005), an artist contributes a piece of work, and managers decide when the time is right to put it on the market. The proceeds are then divvied up: 20 percent for fees, half of the remainder for whoever created the work, and the rest divided among all the artists in the fund.

Of course, it’s one thing to hedge 249 Bevans against one Gauguin. It’s quite another to choose 25 virtually unknown artists and hope that one or two nail the art-market jackpot. Yet that’s just what investors Moti Shniberg and Dan Galai are doing, with the help of David Ross, former director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, who tells Wired, “It’s all about finding the X factor. X doesn’t equal talent. . . . X equals the potential to hit it big.”

Free-market speculation has always been an aspect of the art world. But Shniberg and company, while they’re more altruistic than most investors, are part of a larger trend to, as Suzanne

McGee puts it in Barron’s (April 18, 2005), “treat art as you would any other asset.” Several start-ups with high-power pedigrees (Merrill Lynch, ABN Amro, Christie’s) are hoping to do for the art market what mutual funds and similar investment vehicles did for the stock market. They want to convince investors to put their money “not in a single sculpture to stand in your entrance hall but in a diversified pool run by savvy managers with decades of experience.” In this case, of course, the beneficiary isn’t the artist, but the investor.

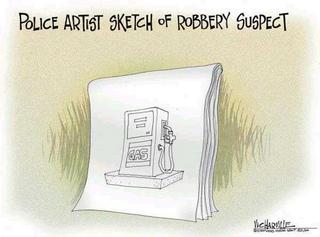

The prolonged downward spiral of the New York Stock Exchange has many moneybags poking around galleries looking to unload a few bucks they might otherwise have spent on oil stocks. In 2004, sales at the art auction house Sotheby’s set records across the board (and drove the company’s stock prices higher). Moreover, recent research shows that the kind of diversified art fund examined by Barron’s might, in fact, outperform stocks. Two widely cited studies have tracked decades of art sales against the S&P 500. Their conclusion: Art wins. The implications are interesting, to say the least. Art history requirements for MBAs? Or how about a trading floor for artistic futures? And what about that starving artist stereotype? Could a fat and con tented Gauguin (who, incidentally, gave up a career as a stockbroker for art) have painted as well as the syphilitic and suicidal wreck we know and love? Shouldn’t you suffer for your art? “It’s silly to say someone is a sellout,” asserts the critic Lucy Lippard. “Everybody is a sellout. Art has no context in this society, so it’s forced into the capitalist context, the marketplace. The only way to be supported is selling it—that goes for people who are selling it on the side of the road up to the most famous galleries in the world.”

The real disconnect, in other words, is between this economic reality and the impulses and imperatives that inspire art in the first place: Art is a product of creativity. Creativity is a manifestation of a range of desires— from self-expression to formal concerns to cultural critique. What’s not clear is whether creativity can survive the pressures of the marketplace.

Of course, popular music, Holly wood films, television, and even commercial advertising are all products of the marketplace. So maybe the real question is whether we want to further conflate the categories art and market-driven culture. Or, more to the point, if we want Wall Street brokers to be tastemakers.

Joseph Hart is a contributing editor of Utne.